At 4:50 p.m. on May 25, 2024, a security camera in a Hutchins State Jail dorm catches Jackie Wiley standing in his white jumpsuit at the back of the large communal room he shares with dozens of other men. The 52-year-old Dallas native, known around the lockup for his bubbly humor, is talking with others sitting on a bottom bunk. Suddenly, his legs start shaking—to some, it looks as though he’s been struck by lightning. He teeters and falls, hitting the concrete floor.

Ninety seconds pass before a nearby prisoner jumps down from the top bunk and grabs Wiley by the torso, pulling him closer to a large fan. It’s a hot afternoon, with temperatures reaching 92 degrees outside, and there’s no air-conditioning here. Some men gather around Wiley—who has a history of seizures and asthma but visited the infirmary only 27 hours earlier and seemed healthy—as he rolls onto his stomach and begins to vomit. Two more minutes pass. When Wiley continues struggling to breathe, several people bang on the doors and windows, shouting, “He’s down!”

A fellow inmate, who’s on custodial duty in a nearby dorm, and a guard respond. The prisoner begins CPR. Another bystander clears out Wiley’s mouth to help him breathe, as his face turns purple.

At 4:57 p.m., medical staff are notified to respond to an “inmate on the floor unresponsive.” At 5:01, 11 minutes after his collapse, staff take over resuscitation efforts. Another guard administers Narcan—because this looks like an opioid overdose—but nothing happens. They put Wiley on a stretcher and rush him to the infirmary, where they’re met by members of City of Hutchins EMS, who take over at 5:08.

The guard is proved partly correct: Wiley is in the throes of an overdose—but not because of opioids. One year after being locked up for possession of meth, he’s obtained and smoked a synthetic cannabinoid commonly referred to as K2, which has no known reversal drug.

At 5:37 p.m., Wiley is pronounced dead at the infirmary. He was expecting to see his wife, a nursing assistant, the next day. He could have been released as early as December 2024. Instead, he died of an overdose of a drug he’d started using behind bars, one he’d told his wife was unchecked in his unit.

K2 is a psychoactive drug that targets the same part of the brain as THC, but the effects can be far different from those of marijuana, in part because many doses have been heavily adulterated with harmful chemicals. Synthetic cannabinoids don’t make up a large part of the free-world drug market, but at least one study found their use is increasing. K2, also referred to as “spice,” has been circulating in prisons and state jails since at least 2017.

Worse, the number of people whose deaths in state jails or prisons were attributed to synthetic cannabinoids increased from 16 in 2023 to 65 the following year. And this is likely an undercount, given that synthetic compounds can be difficult for labs to detect in standard drug tests or postmortem toxicology screens.

The rise in K2 deaths is part of a disturbing trend: Between January 2020 and July 2025, at least 189 Texas prisoners died of drug-related causes—and each year through 2024 was deadlier than the last. In 110 cases, synthetic cannabinoids were confirmed or suspected to have caused or contributed to in-custody deaths, according to a Texas Observer analysis of reports filed to the state’s Office of the Attorney General. Most overdoses were attributed to drugs illicitly smuggled into state lockups. Another 128 people in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) died of accidental or unknown causes during that period that could have been linked to drug overdoses, based on symptoms or circumstances described in related records, the Observer’s analysis found.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG)—governed by the Texas Board of Criminal Justice but independent from TDCJ itself—launched an investigation into Wiley’s overdose the very same night. That’s routine in such cases, according to Amanda Hernandez, communications director for the prison system. “TDCJ has zero tolerance for illegal substances and contraband,” she said. “If any person, whether that is inmate, staff, volunteer, [or] visitor is caught bringing illicit substances into any TDCJ facility, the Office of Inspector General is immediately called to investigate.”

Hutchins saw three drug-related deaths in 2024, the most of any state jail. Wiley was one of two confirmed K2-related deaths at the unit that year: Daniel Jacob Sauceda, 22, died six months later of synthetic cannabinoid toxicity. Another man, 62-year-old Victor Blanco, died April 18 after overdosing on prescription drugs.

Hutchins is part of a state jail system created in the 1990s primarily to house people convicted of relatively minor drug and property crimes. State jails were billed as places where low-level criminals serving short sentences, like Wiley, might get help with addictions. But, over the years, experts say that state jails experienced a kind of mission creep, as higher-level criminals were locked up at the facilities and as drugs seemingly circulated freely. With a high proportion of drug users, large and crowded living areas, scant educational programming, and less advanced medical facilities than prisons, these units can become breeding grounds for drug use.

For those who do make it to their release dates, a 2019 state House committee report found that their time has typically been wasted: “State jails … merely warehouse inmates who unproductively serve out their time until being released, with no new resources, into the same conditions that led them to jail in the first place—most often, drug addiction and poverty,” the report reads, concluding the facilities should be abolished or “overhauled in every respect.”

For those who don’t make it, their family members—like Wiley’s widow, Chrystal Stanley—are often left with questions that go unanswered. Among them: Where did the drugs come from? And why didn’t help come in time?

As a child, Jackie Wiley already had a habit of testing limits. His sister, Loni Shults, a year older, recalls their childhood in the East Dallas suburbs as a montage of her exclaiming: “No, Bubby, don’t do that!”

Around age 3, Wiley rode a toy motorcycle down a set of outdoor stairs after watching stunt daredevil Evel Knievel on TV. He once started a small fire in the house so his toy fire truck could swoop in to the rescue. Occasionally, he stuck keys in electrical sockets to make his hair stand up.

Beneath that wild streak, Shults remembers, was a tenderhearted and protective kid. Wiley loved animals so much that he was always moved to tears by the heroic journey of Rudolph the reindeer. He once stepped in to protect their older brother from their abusive stepdad, who then shoved Wiley to the floor and gave him a concussion.

Wiley bore the brunt of the stepfather’s physical violence, Shults remembers, though she herself was sexually abused. Periodically, Wiley would try to run away, but she’d find him and bring him back. That changed the year she turned 17 and took the chance to escape. She moved out and married.

In her absence, Wiley’s mischief turned more dangerous. He started stealing stereos from cars, then the cars themselves. He got into drugs, first marijuana, then harder stuff. Eventually, he became hooked on methamphetamines. “I believe he did it because it was his outlet from what we were going through,” Shults said. “If you’re gonna get in trouble anyway, why care?”

He was first arrested at 17, and more busts followed. He entered into a volatile marriage and in 2005 and 2008 was convicted on charges related to domestic violence. His ex-wife, Theresa Wilson, told the Observer they loved each other but his drug use caused problems. “I wouldn’t describe him as a violent person,” she said. “I would describe him as being addicted to something that controlled his life.”

After going to prison in 2017, Wiley tried to turn his life around inside, taking every class he could, Shults said. Despite his troubles, Wiley had previously done well in school. He became certified as an electrician and an HVAC technician. In the years after his release, he stayed clean and found work. In 2020, he told his sister he’d met somebody pretty and nice. “I think you’re gonna like her,” he said.

Chrystal Stanley, a 39-year-old mom, managed a hotel in Pilot Point, a small city in Denton County. She met Wiley when he got a gig there doing electrical work. The spark was mutual. He was handsome—with bright blue eyes and a disarming smile—and she appreciated his wit. “My little science nerd,” she called him.

They fell in love and quickly merged lives. They remodeled a mobile home in Denton. He attended Narcotics Anonymous as a condition of his parole, and, for a while, he seemed to have overcome his addiction. Stanley said he wouldn’t use drugs when they were together, but eventually she realized he would sometimes “sneak and do it.”

As an adult, Wiley had developed epilepsy, which his sister suspected stemmed from his drug use or head injuries from being abused. In 2022, he suffered a seizure behind the wheel while driving to see his sister in Fort Worth. He struck a trash can, steered his 2003 Toyota to the roadside near a church, and passed out. When he awoke, Johnson County sheriff’s deputies were knocking on his window.

No one had been hurt, but a neighbor had called in a suspicious vehicle after seeing Wiley apparently asleep inside. Still confused, he told the officers he didn’t remember what happened or how he’d arrived at the church. They didn’t call an ambulance. Instead, officers searched the car after spotting marijuana on the dashboard. They found two small bags of methamphetamines. He was charged with possessing less than a gram of meth, which Texas considers a state jail felony.

Because of prior crimes, Wiley was sentenced to four years. He was initially sent to the George Beto Unit, a maximum security prison in rural East Texas, before being transferred to Hutchins, about 10 miles south of Dallas.

His wife and sister welcomed the change. Hutchins was smaller, closer, and—they believed—safer.

Texas lawmakers created state jails in 1993 in an attempt to relieve prison overcrowding and reduce backlogs of people who’d been sentenced and were awaiting prison transfers in county jails.

During the 73rd legislative session, lawmakers overhauled the penal code, designated certain crimes as state jail felonies—for which the maximum sentence is two years—and created a network of shorter-term detention centers. Then-Senator John Whitmire, now Houston’s mayor, marketed the legislation as a tough-on-crime initiative. Other prisons would have more room for violent criminals, whom Whitmire referred to in a 1993 committee hearing as “the ones we wanna lock up and throw away the key.”

Because so many of the nonviolent crimes that sent people to state jails were drug-related, Whitmire and others saw an opportunity to create secure rehabilitation centers. In the same hearing, Whitmire predicted that state jail felons would “have a chance to be rehabilitated off drugs and alcohol, hopefully where we won’t have a revolving door.”

In 1995, the first few units opened, including Hutchins. By 2003, these facilities housed 16,000 people for state jail felonies alone. But that subpopulation fell by nearly 40 percent between 2010 and 2018. Today, Hutchins is one of 13 public state jails run by TDCJ, in addition to three private facilities the agency oversees. Collectively, the units house about 20,000 prisoners, but a greater share were convicted of more-serious or violent felonies. The Hutchins unit houses about 2,000 men.

Currently, eight of the 16 TDCJ jails offer initiatives designed to help people recover from addiction issues. Prisoners serving time for state jail felonies can earn “diligent participation credit” for going through rehab programs, which shaves time off sentences.

But Marc Levin, chief policy counsel with the nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice, said state jails programs aren’t achieving their goals. People are often in state jails for too short a time to achieve meaningful rehabilitation, he said. “It makes it more difficult to have people engaged in pro-social and positive activities,” Levin said. “When they’re not engaged in that, then that’s more of an opening for drugs and contraband and things like that.”

Hutchins offers both a state jail substance abuse program and a pre-release rehab program. But Wiley, who’d struggled with addiction for decades, didn’t participate. He wasn’t required to, and he didn’t opt in, according to Stanley. Many in similar situations don’t.

In 2018, the Texas House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence evaluated whether the state jail system had lived up to its intent of reducing “prison populations and recidivism by tying treatment tracks to both probation and incarceration.” This resulted in the damning report that called for the system to be overhauled or abolished. The committee—led by Democratic Chair Joe Moody and Republican Vice-Chair Todd Hunter—found that treatment programs were never fully funded or developed and that recidivism rates remained high.

Moody told the Observer that nothing about state jails has really changed since. “The legislative idea behind state jails several decades ago was a gap-filler that would provide rehabilitative programming,” he wrote via email. “These facilities never lived up to that promise because of underfunding, mission confusion, and a design where people just process in and out before they can get even the limited help that’s on offer.”

Although Wiley didn’t seek treatment at the state jail, he often complained to his wife about how abundant K2 was, especially in his dorm. He told her that drugs were as prevalent there as they had been outside. But he promised her he wasn’t using K2, even when she confronted him by phone about odd behavior.

Data backs up Wiley’s assertions about K2’s prevalence in TDCJ-run facilities. Between 2022 and 2025, people in prisons and state jails submitted at least 70 formal complaints related to K2 in their units to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman, which handles noncriminal matters in state jails and prisons. By comparison, only eight complaints mentioned methamphetamines.

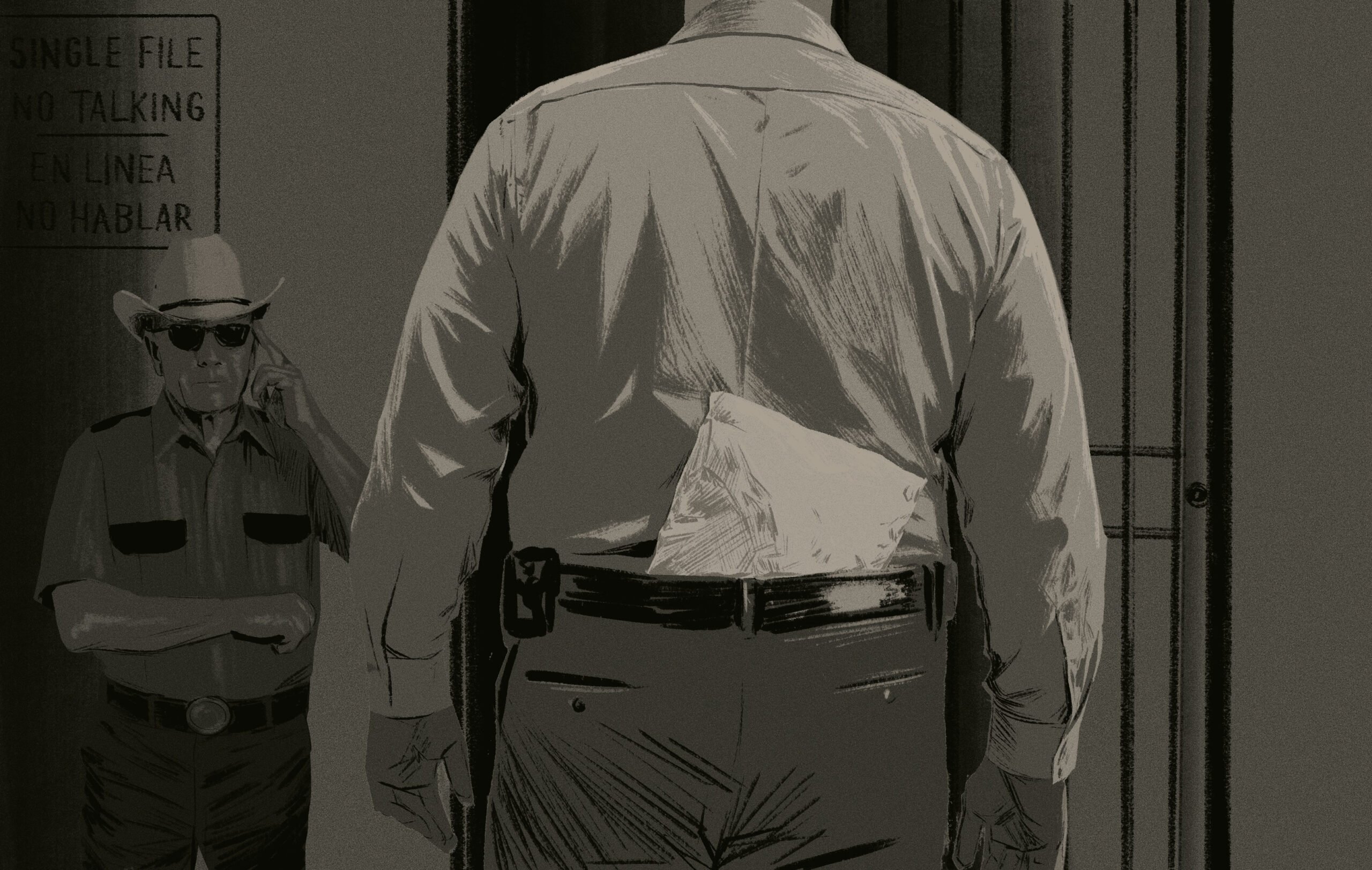

Hernandez, the agency spokesperson, said all visitors, volunteers, and staff are searched when they enter any unit, and prison employees use drug-sniffing dogs and scan physical mail.

Still, drugs are successfully hidden in mail, smuggled in by visitors, and brought in by guards, as TDCJ’s ongoing staff shortages complicate enforcement and screening efforts.

In 2023, the agency enacted a rare systemwide lockdown in response to a spike in contraband and violence. Between January 2024 and July 2025, law enforcement brought charges against 321 prisoners, including 11 in state jails, for having a prohibited item, engaging in organized criminal activity, or possessing drugs. Two charges originated at Hutchins, but neither appears related to Wiley’s overdose.

Since January 2020, 219 TDCJ employees from 58 units have been arrested for drug-related crimes, according to reports obtained through a public information request. The charges included bribery, engaging in organized criminal activity, and having a prohibited substance in a correctional facility. In that time, no guards from Hutchins were arrested.

The OIG investigation into Wiley’s case found that prisoners were paying for drugs with online money-transfer services like Cash App and Venmo and even Walmart money transfers, with one unnamed prisoner naming the source of drugs as: “Guards.”

Chrystal Stanley last spoke to her husband one hour and 15 minutes before he was pronounced dead.

It was Memorial Day weekend, and they were excited for their visit the next day. But Wiley ended the phone call early, at 4:22 p.m., which was unlike him. He said he wasn’t feeling well, was going to lie down, and would call back.

When the phone rang later that evening, it was the warden with the news.

Stanley told the warden he was mistaken—she had just spoken with her husband. “Yes, ma’am, I’m so sorry,” she recalls him saying, as shock set in.

A day later, a TDCJ chaplain sent Chrystal a letter about Wiley’s death. It simply said he’d died of cardiac arrest. And she noticed what seemed like a copy-paste error: It referred to her husband as “Victor” (the name of the man who’d overdosed at the jail the month prior). She thought: “It doesn’t matter to them. But for me it does.”

That weekend, she started looking for witnesses and answers in a Facebook group for people with loved ones at Hutchins. She had little information about what led to her husband’s heart failure, and her mind reeled with theories. Other women commented that they’d heard that someone had collapsed from a drug overdose. One privately messaged her, saying her son wanted Stanley to know that medical staff “does not take their job seriously.” Another said her loved one reported that guards “don’t even care that people are on drugs in there.”

Prison officials told Stanley she couldn’t see Wiley’s body at the unit that Sunday. They said she could call the Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office, but it would be closed Monday for the holiday.

She and Wiley’s sister, Shults, finally viewed his body at a Dallas funeral home on Tuesday. Stanley took pictures during the hour she had, feeling as though she needed to document the state of the body. She believed it was possible that his death wasn’t accidental, and she didn’t trust that she’d get detailed answers from the prison system.

Wiley’s death hit his sister hard. “He was my baby, man,” she told the Observer. “I’d have done anything for him. I still cannot believe he’s gone. … Anything my brother has ever done did not warrant [this] happening to him.”

Over the prison messaging system, Wiley’s friends told Stanley he had made their lives easier with his humor. They told her Wiley had been looking forward to the visit the following day and that he talked about her constantly.

For the next few months, Stanley and Shults pleaded with prison leaders and with Antwain Ruth, the OIG investigator, for updates. But the probe into Wiley’s death remained open. They sent regular emails asking whether officials had any news about the investigation, but eventually Ruth stopped responding.

On September 10, the OIG’s office received a toxicology report from a Grand Prairie testing lab showing that Wiley had synthetic cannabinoids in his system when he died, and the following month the Dallas medical examiner determined he died from the drug’s toxic effects. No one told Stanley at the time. In early 2025, though, she got another clue when she refreshed the attorney general’s web page of in-custody death reports and saw that his manner of death had been switched from “pending” to “accidental.”

The pieces clicked into place. The messages from the families. The fact that when she’d retrieved his box of personal items from the warden’s office, including various handwritten notes and commissary receipts, she found an odd piece of cardboard with three shapes cut out of it, which she learned could have been used to measure doses of K2-soaked paper that are then torn up, put into joints, and smoked.

After nearly a year of begging for information, Stanley signed up to address the Texas Board of Criminal Justice. She wrote a brief statement, given the limited time allotted, and planned to say how hard she’d pushed to get information and how little she’d received. One line read: “Isn’t it ironic that the same system that punished him for his addiction on the outside continued to supply and feed it on the inside?”

She arrived at an Austin hotel conference room last April. Then, before she could speak, she was pulled aside by prison staff. They offered to show her the OIG’s report for the first time and to play security footage of her husband’s collapse. She accompanied them to an office, where she watched the moments that led up to her husband’s death.

That day, Stanley got more information than she had in 11 months, but holes remained. She still didn’t understand why it had taken so long for her husband to get medical help, or why no one was punished for supplying the drugs that killed him.

The OIG had finished its investigation a month prior, she read. A guard was named as a potential suspect but denied involvement. The employee’s file showed multiple disciplinary actions—but none related to Wiley’s case. Despite having a suspect, the agency concluded: “During this investigation multiple efforts were made to identify the individual alleged to have smuggled drugs into the facility; however, no information was provided that would assist in identifying the individual.” Nothing was referred to the Dallas County district attorney for prosecution.

The video also showed Stanley that potential evidence may have been lost when prison officials failed to secure the death scene: Footage caught several prisoners cleaning up shortly after Wiley was carted away to the infirmary. Having learned all this at last, she never delivered the statement she’d planned.

Sometime after her husband’s death, Stanley began a ritual to remember him by. On Saturdays, she starts counting seconds at 4:55 p.m., the exact time Wiley fell to the floor. She puts her hands to her chest and beats a rhythmic dun-dun. “That time just ticks. Eats me up alive.”

Over a year later, Stanley, who’s working in hospice care these days, still looks at the clock and counts. And she still has unanswered questions, like, “Did they do everything they could do to save him?”

In her quest for answers, and to keep Wiley’s memory alive, Stanley found out something else about her husband—something that surprised even her.

Among the items in the box she retrieved from the warden’s office were handwritten wedding vows. The two already had a common-law union, but apparently he’d been dreaming of a formal marriage ceremony.

Wiley promised to put her needs and wants before his own and, with a touch of his usual humor, to make sure she could have her nails done as often as she liked.

“I further vow to take her into my heart,” he wrote, “and in sickness and health, hard times and easy times to be her strength and never lie, deceive, nor abandon her no matter what the circumstances.”

The Law & Justice Journalism Project provided support for this story.

The post In Texas State Jails, a Rising Death Toll and a Broken Promise appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Want more insights? Join Working Title - our career elevating newsletter and get the future of work delivered weekly.