What to Know

- A notification about an earthquake Thursday morning in western Nevada near the California border was a false alert, the USGS says.

- The quake alert generated by the ShakeAlert early warning system sent message to users on the West Coast.

- The USGS said it is looking into what went wrong, but noted such false alerts are extremely rare.

- The agency is investigating, among other things, the data provided by sensors in the field and the processing algorithms that use the information to generate the alerts.

- There are several scenarios that might cause the early warning system to generate a false alert.

A notification about a magnitude-5.9 earthquake in western Nevada near the California border Thursday morning was a false alert, the USGS said.

The quake alert generated by the ShakeAlert early warning system and an entry on the USGS web site indicated an earthquake near Dayton, Nevada, about 10 miles northeast of Carson City, Nevada and 30 miles northeast from Lake Tahoe. The alert appeared on the USGS earthquakes map, but was deleted soon after and replaced with a message.

The ShakeAlert notification was delivered at 8:06 a.m. PT.

“The ShakeAlert EEW system released an incorrect alert for a magnitude 5.9 earthquake near Reno and Carson City, Nevada,” the USGS said. “The event did not occur, and has been deleted from USGS websites and data feeds. The USGS is working to understand the cause of the false alert.”

The same message was posted to the ShakeAlert early warning system web site.

The system — a safety tool for roughly 50 million permanent residents and tourists on the West Coast — detects earthquakes that have already started and estimates location, magnitude and shaking intensity. A ShakeAlert message is sent to users when the earthquake is large enough to meet USGS alert thresholds.

Even a few seconds of warning before shaking can have a dramatic contribution to public safety, including time to drop, cover and hold on.

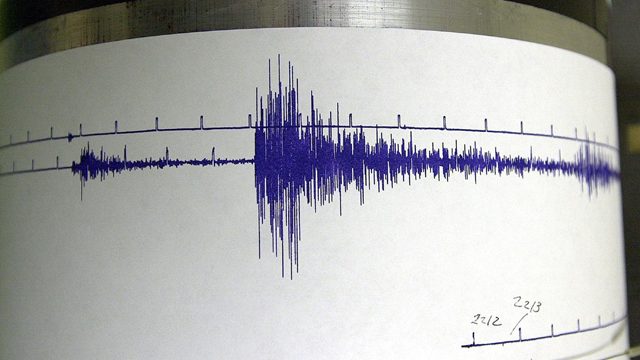

The system uses sensors spread over wide areas prone to earthquakes on the U.S. West Coast. Data collected by sensors from the seismic waves produced by earthquakes is transmitted to a ShakeAlert processing center, where location, size and shaking intensity are determined in seconds. Alerts are then sent to ShakeAlert users by technical partners.

The California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services said early warning alerts were sent to widespread parts of Northern California.

“Cal OES is aware of a false reading from U.S. Geological Survey at 8:06 a.m. today that triggered an Earthquake Early Warning alert to a broad audience in Northern California,” the state agency said. “USGS has confirmed to Cal OES that no earthquake occurred in Northern Nevada this morning. Cal OES is coordinating with our Nevada and federal partners to understand exactly what the federally run monitoring system detected and why.

“That national system is operated by the U.S. Geological Survey, not the State of California, but we rely on it every day to help keep our communities safe by providing critical, life-saving information when seconds matter.”

MyShake, an app that uses the ShakeAlert system, said in a post on X that system has delivered more than 170 “real alerts” since 2019.

“This incident is both unprecedented and rare,” the post continued.

Robert De Groot, a physical scientist with the USGS, said Thursday afternoon that it still wasn’t clear what went wrong.

“One thing we know for sure is that the ShakeAlert system processing side and the alert delivery side, meaning the part that takes the data from the field and then hands it off to folks like MyShake to actually deliver the alerts, performed as designed,” DeGroot said. “What we’re looking at is that interface between the data that came in from the sensors in the field and the processing algorithms that actually use that information to generate what would eventually end up as an alert on the other side.”

De Groot also runs the USGS X account.

“I’ve only seen the beginnings of the replies from people, which are totally justified,” he said. “We know that people get very concerned, and we take those concerns very seriously.”

There are several scenarios that might cause the early warning system to generate a false alert.

For example, location algorithms sometimes misidentify reflected and refracted seismic waves created by one earthquake, which can turn into events far from the quake’s location. Noise in analog telephone circuits used to bring data from seismic sensors to computers also can be misidentified by automated systems as earthquakes. Software aimed at locating local quakes can sometimes mislocate a large earthquake on the other side of Earth, deep beneath the seismic network, the USGS noted.

“Adding to this complexity, there are multiple seismic monitoring networks that contribute their earthquake locations and magnitudes to the ANSS system,” the agency said on its web site. “These networks use different data and algorithms to locate the earthquakes, and sometimes the spatial separation of the contributed locations is so large that our systems interpret the independent solutions as distinct earthquakes of similar magnitude and location. In this situation, a delete message will be sent for one of the earthquake solutions but an earthquake did occur.”

The agency also notes there’s a trade-off between the speed of a notification and number of false alarms.

“The faster we release earthquake locations and magnitudes, the more likely it is that the information may be erroneous,” the USGS said on its site. “Experience demonstrates that imposing more restrictive quality standards prevents the release of legitimate earthquake information.”

This story uses functionality that may not work in our app. Click here to open the story in your web browser.

Want more insights? Join Working Title - our career elevating newsletter and get the future of work delivered weekly.